Jameel Mohammed's creations always begin with a sketch. With each subsequent drawing, he capitalizes on initial imperfections, or "mistakes" as he deems them. “I'll look at it from the front and say, ‘Wait, couldn't this shape be a bag?’" he muses. (That "shape" was initially intended to be a vase.) Mohammed only diagnoses the impetus behind a series of these creations in retrospect. “If the [feeling] is hopeful with a tinge of sorrow, which pieces were inspired by the time I was watching a documentary about [colonialism]?” Whether it's through ready-to-wear, jewelry, or objects, the designer invokes this seemingly backwards method to tackle questions around the Black experience through his design.

The Chicago native launched his brand Khiry his junior year (2016) at the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied political science and behavioral economics (though he never completed his degree). He debuted with jewelry for pragmatic reasons. Internships at Narciso Rodriguez, Nicole Miller, and Barneys through high school and early college helped him to understand what it takes—specifically in terms of business scale—to create ready-to-wear deserving of the luxury descriptor. In 2021, he introduced ready-to-wear—if you can call it that. The ensembles featured materials ranging from feathers to cannabis packets to deconstructed American flags. His outlandish designs prioritize shock value over creativity for good reason. Mohammed has an informed reverence for the complexity of a simple yet perfect garment, for which he doesn't yet possess the means. “I think my intention at this stage of my business is to demonstrate and create items that can sit in my archive and be the foundations for when I make those wearable garments,” he says.

The 27-year-old acknowledges the fashion industry's troubling logistical barriers (as any designer knows, an editorial or celebrity placement does not guarantee business success), but no such thing exists in the way of his creativity. Throughout the pandemic, Mohammed experimented with sculpting. He collaborated with Fleuriste St. Germain to create a pop-up shop fit for a floral enthusiast. And in multiple of his endeavors, the multi-hyphenate talent has moonlit as a jazz singer. So where is the consistent factor in this un-siloed approach to creativity? Mohammed resolved his thoughts on this question during our interview. “I think that it comes from a place of understanding that the function of art for Black people has rarely either been read as or actually been purely aesthetic production.” The work Black creatives make is typically categorized as political at the onset. “And there's also inherent politics to any production in any space,” listing trade relationships, aesthetic priorities, and production mechanisms as evidence. "If I can't control the global economy, perhaps I can inspire and create space for questions about why it's out of our control."

His first taste of this world of fashion he's now deconstructing at an all-encompassing scale with was highly personal. A favorite New York-based aunt, helped him to realize his innate sense of style—at the J.Crew in downtown Chicago. There, they crafted the middle schooler's new look—”preppy suburban, but cooler"— with jewel-toned sweaters and corduroys. "It was both irreproachably acceptable, and expressively flavorful," Mohammed reflects. He first realized the power of fashion in the reaction of his peers. “I saw the difference of how I was being regarded in the community by everyone, teachers, kids, parents, random person on the street," he recounts, "when I was in my cords with my little corrugating graph paper shirt, in my little cashmere emerald sweater.”

Fast forward to high school and he was going to Borders, collecting Man About Town and Bullett. Thrift stores simultaneously lit the fuse of inspiration and had him throwing down quick sketches while he manned the phones at his local pizza restaurant. On his own body, he was indulging in classic vintage finds, tweaked to his liking. The style-obsessed teen was wearing an "oversized shirt, super tight cords that had shrunk in the wash a few times, rolled up with loafers and white or red or crazy socks," he explains. "I would eventually spray paint the cords with bleach so they would have this kind of galaxy effect. Or maybe a mink jacket on top, and then a painted American flag on a white blazer that I cut the sleeves off for a vest. It got more and more punk over time."

As his professional career bloomed, the 2021 CFDA Vogue Fashion Fund Finalist and Forbes 30-Under-30 recipient distanced his personal outward expression from his designs. Today, Mohammed errs more towards the stereotypical notion of a subdued artist's ensemble. “I think my uniform is a reflection of the life I lead," he says. "I want to be kind of unreadable in most circumstances that I'm in, and really ultimately able to move between worlds without sticking out too much in any place.” When we spoke he donned a simple salmon t-shirt. He also favors the Gap—mainly because they are one of the few brands that accommodate his 6'5" frame. He’s also dressing for his current lifestyle—”I'm going to the bodega and then to the studio and then to the bodega”—save when he attends major events (like the Met Gala which he attend in 2021). That’s when he gets to feel what it’s like in his own designs. He pauses when I ask how much he designs for himself. "I would definitely not say that I'm consciously, per se, thinking about myself," he posits, "but if you looked at my sketches, you'd be like, "Girl, this is you." The designer is referring to the lanky model consistent through his figure drawings. He also often models his own pieces on his Instagram page. “I [just] design things that I happen to look really, really good in,” he laughs.

"This [dress] was about the idea of wanting to be shiny, in some way, like associating being in a shiny something or other as a high water mark in your career. It's such a universally aspirational image, if you see someone, especially a woman or a femme-presenting person, in a shiny gown, you know they must be doing something important. I also wanted to do that in a material that was referential to childhood experiences. it's a very local interpretation of that desire for shine and for brilliance. [The pants] are Gap. I have a 36-inch inseam, and a 30- or 32-inch waist, so it's nearly impossible to find any pants. The Gap brands always have long sizes."

"I don't care how I look, I just want to make things and put them on everyone else. That is my only focus."

"This is constructed of 15 or 16 whips. It's a heavy piece, to be honest. It's about the question of whether and how applicable forms of fantasy are for everyone, but also the celebration of Black people's will to find space for themselves within any community, to get beyond external contradictions of your fantasies to get to the root of who you really are, and what you really desire. For yourself, but also for the world."

“I've always known that I wanted to go into clothing, it was never really a thought. At the beginning of the pandemic, I started to just really reconnect with my roots as an artist, even before my interest in fashion. I came to understand my interest in fashion as partly circumstantial. I personally experienced the power of fashion in my life. I could imagine myself making a reasonable career in fashion [whereas] art felt too abstract to try to make a career out of it."

"There has always been an inherent politics to Black production in any space. And there's also an inherent politics to any production in any space. I think the core of my practice is acknowledging and seeking to wield cultural influence through asking questions with the objects that we make. It's kind of like a backwards production, right, like if I don't own the means that everyone's production comes to us by, if I can't control the global economy, right, perhaps I can inspire and create space for questions about why the rest ... why I can't control it, why we can't control it, why it's out of our control. And how that might be changed, who does that harm, and in what ways? Historically, contemporarily, and how might we change that?"

"That vest is from a look called Imagined Community, which is like a political science term for a nation. That's really the strength of what holds a national boundary together; there exists a group of people who imagine themselves to be in community. And so all of these are different African countries, but also Caribbean countries, there's the African American flag in there. So it's really about an imagination of a Black world and of a community linking those countries. But there's some threads that are hanging. There's some visible tenuousness, which is like my favorite thing to play with. I love a thing that looks like it's only held together by the strength of our imagination in this moment, and it could just be destroyed. Think about that. If it is tenuous, but it is valuable, then people will preserve it. If it isn't this tenuous, and it isn't valuable, then it will be destroyed, and that's the question of the piece on some level."

"I don't want to impose my body [on my designs], but I also want to feel like my body is okay, which is something that I haven't always felt. So it's definitely a negotiation. And I'm still learning."

"By sophomore year [of high school], I was like, 'I have no idea what assignments I have, so I don't even feel bad for missing them, because I'm really just like, what am I wearing tomorrow?'"

"This is the Bluest Eye dress, it's from, the collection is the pieces that we shot from our Fantasy Suite: Fragile, Facile, Futile, Fruitful? It's the third [chapter] in like a trilogy that's about assessing these different trauma responses of fight, flight, or fantasy, and how they can either aid us in our healing or be a kind of avoidance mechanism. The Bluest Eye look is about the aspiration for whiteness and for white features, and also about The Bluest Eye, by Toni Morrison."

Shop the Story:

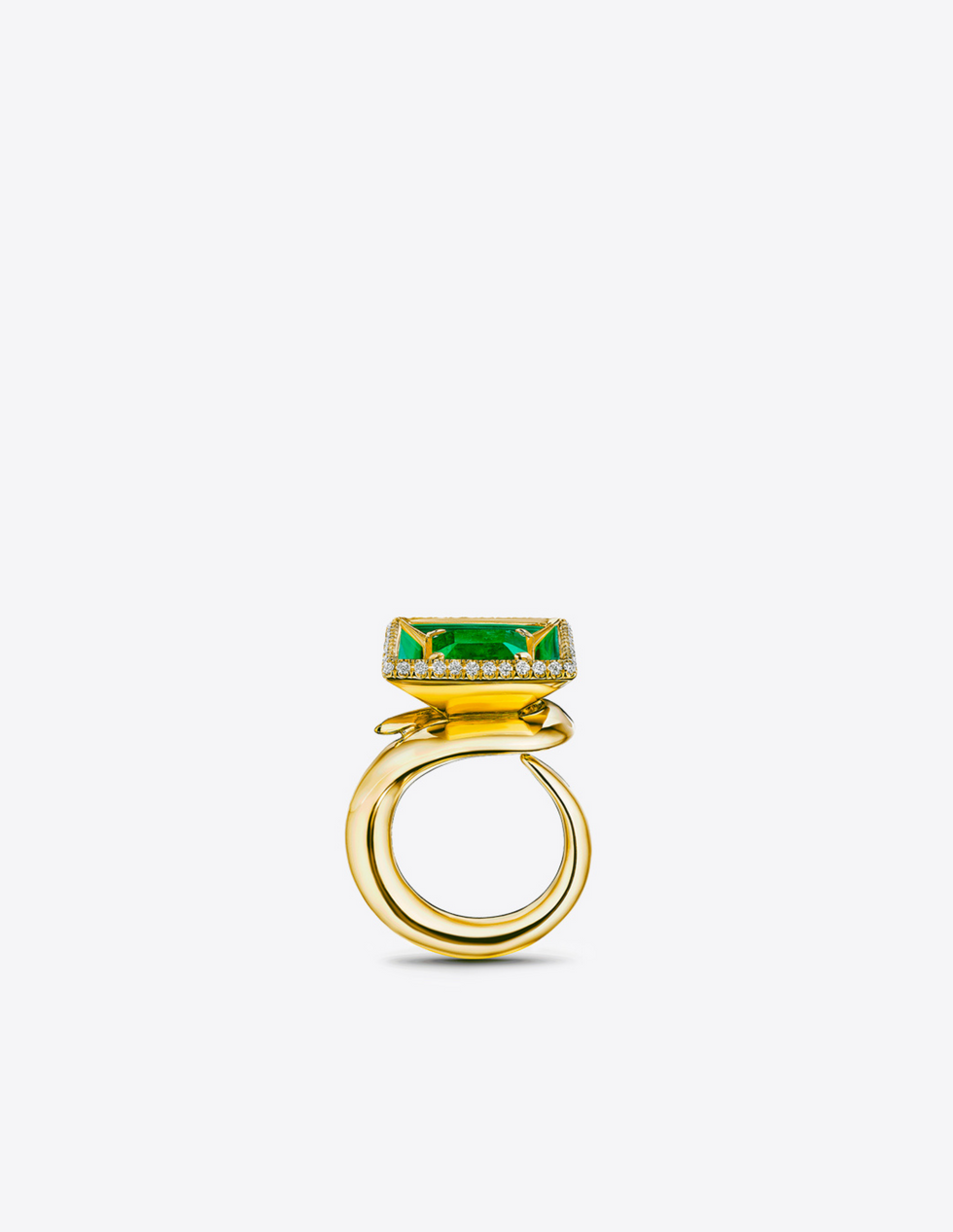

Pavilion Ring

Khartoum Studs Embellished in Polished Gold Vermeil

Comme des Garçons PLAY High Top Sneakers

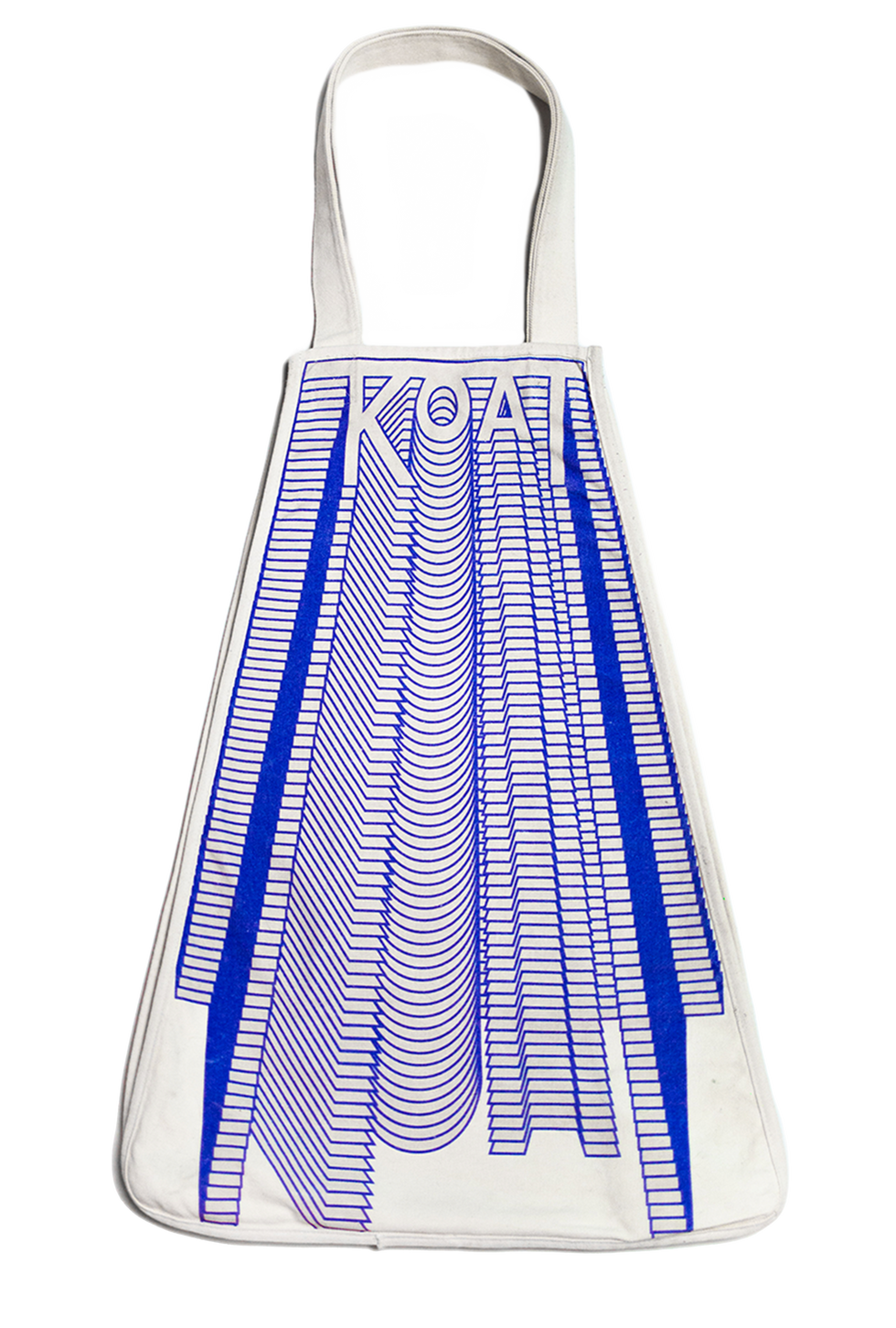

Tote XL

Staples Cuff in 18K Gold

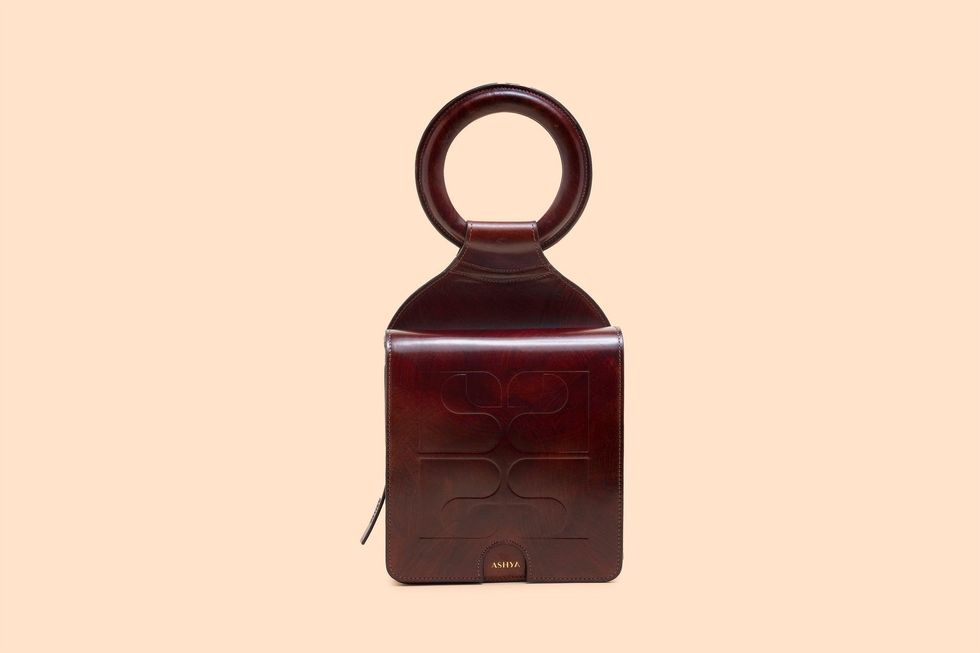

Slingback Mini Bag in Trilogy

Want more stories like this?

Stylist Ian Bradley's Closet Pays Homage to Early 2000s New York Nightlife

Sherri McMullen's Closet is Home to Dries Van Noten, Simone Rocha, And—Of Course—Christopher John Rogers

Inside A Brooklyn Closet Where Gender is A Construct and Sequins Are A Must

0 Comments