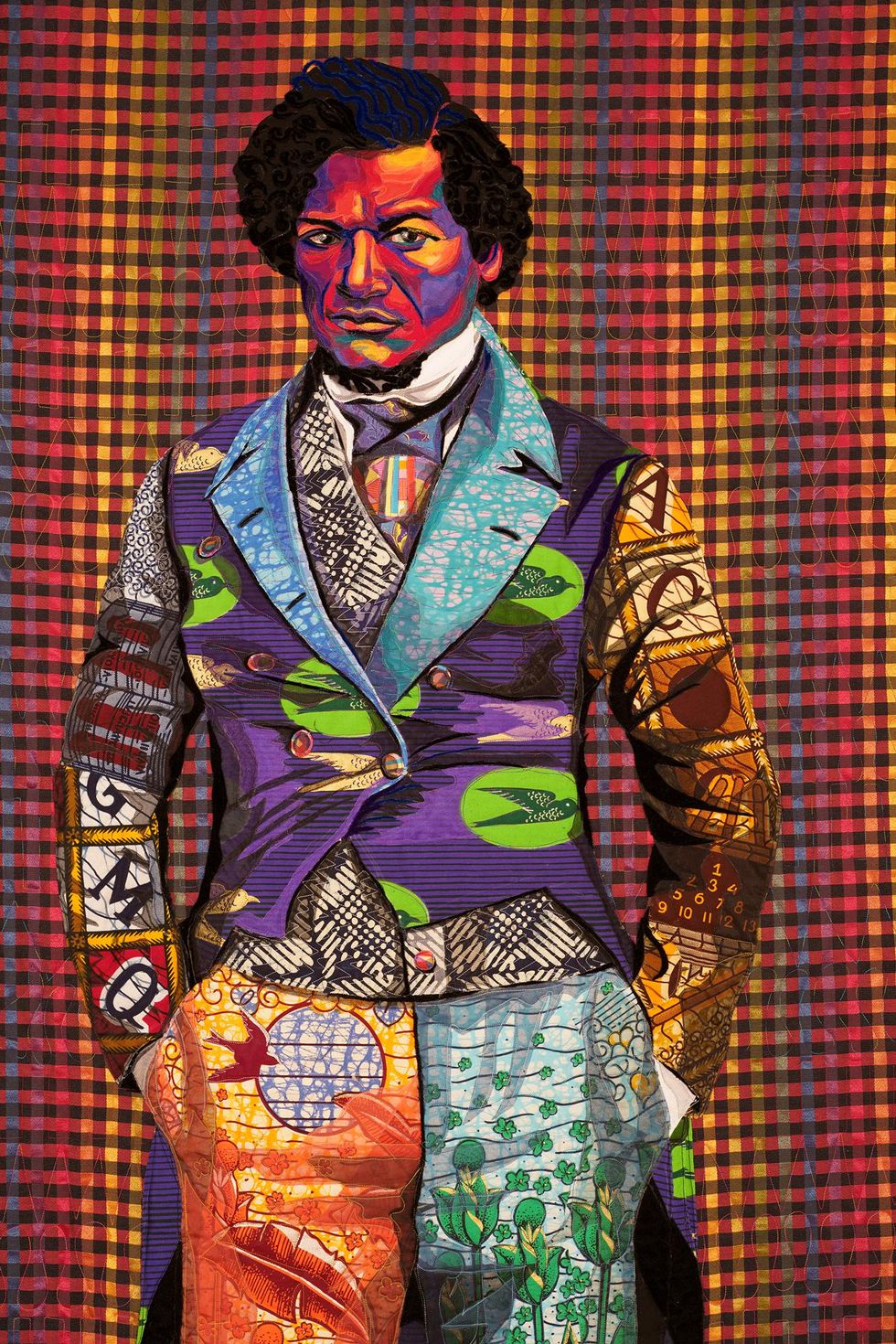

Portraiture has an unforgettable way of capturing the emotion, the stories, and the circumstances of the subject in frame. For a moment in time, the viewer can peek into this represented life, although it is but a glimpse of the many trials, tribulations, and tales they embody. The New Jersey–based fiber artist Bisa Butler knows this convoluted idea well, after over 20 years of showcasing subjects that are both living and dead, known and forgotten. Her authentic intent guides her to share a visual story of Black lives who are and were ignored from history. Through quilted works of bright colors and patterns, Butler sets the record straight and communicates the truth from her community's point of view. Each portrait offers veracity and honesty to present what hasn't been acknowledged in mainstream media, the government, or textbooks.

Today, "Bisa Butler: Portraits" is on view through September 6 at the Art Institute of Chicago. Featured in the exhibition are 22 quilted portraits, as well as works by artists who have influenced her, including Romare Bearden, Gordon Parks, and Barbara Jones Hogu of Afri-COBRA. Last weekend, in celebration of Juneteenth, Butler also appeared on OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network for OWN Your Shine: Juneteenth Artist Showcase, which honored prolific Black artists of today.

As Butler works on a large-scale portrait of the Harlem Hellfighters for a museum in Washington, D.C., among other works, she discussed with us how motherhood led to her start in quilt making, what fashion choices and beauty practices she embraces daily, and how her family's history in international and home-grown fashion led to lovingly stitched expressions of the African diaspora.

When you were young, your mother and grandmother sewed clothing inspired by French couturiers. How did this impact your idea of craft?

"My mother, grandmother, and all of my aunts loved fashion. My grandfather was a U.S. Emissary to Morocco in the 1950s, so they raised all 10 of their children there and didn't return until the kids were nearly all grown. Morocco was a protectorate of France, as they had a sultan, but he did not rule. My grandparents had to go to many embassy balls and events, and although they were living the ambassador lifestyle, they were middle-class people. My grandmother—and her daughters, which included my mother—endeavored to recreate French fashions of the day and were partial to Oscar de la Renta, Pierre Cardin, and Christian Dior.

"Later, one of my mother's sisters (my aunt Lydia) became a fashion photographer in New York and Paris. It was common to have designer samples around the house. By the time I was born, the family had resettled in the U.S. and there were always big copies of Vogue, ELLE, and Marie Claire in my grandmother's house. I grew up watching them continue to recreate fashionable outfits following McCall's patterns or making their own designs. My mother made my prom gown based off a Carolina Herrera dress I saw in Vogue. She bought red silk chiffon from the local Indian shops and had to line the hem using fishing wire so that my dress would have a scalloped ruffle like the one I saw in the magazine."

You made a quilt of your mother in grad school from these types of scraps of fabrics, after having your daughter and putting painting on the back burner for a few years. How did that change the trajectory of your career in art and as a mother in the art world?

"I made a quilt of my grandmother while I was in grad school as a gift to her. I first asked her to sit for me, and I painted her every day for a week or so. She was so unhappy with the way I made her. She said I made her look like 'an old, old lady.' I realized that I hadn't recognized that my grandmother still had her vision of herself as a woman that may have been different from the way I saw her as my grandma. I then created a quilt of her because I was taking a fiber arts class at Montclair State University and I could make her portrait out of cloth and satisfy the requirements for my grade. I decided not to create another sketch, but to work from a photo that I knew she loved—her wedding photo that had sat on her dresser for 60 years.

"I used pieces of fabric that reminded me of my grandmother, like a pattern with purple flowers because her name was Violet, lace because of her upbringing as a Catholic schoolgirl in New Orleans, and fabric from her own stash that she had given to me. The vintage fabrics my grandmother gave me were the remnants of all those beautiful outfits they had worn years before in Morocco and West Africa. I created a quilt using dressmakers fabric because that was what I had. The finished portrait ended up being something that my grandmother loved and was made up of bits of her own life.

"I realized after I finished that I had created something new; it was a quilt made up of scraps, but it also was a portrait of a specific person. This portrait was made up of the remnants of a life. As a mother, I could quilt in the presence of my small children and not have to worry about them accidentally ingesting or inhaling fumes. My artwork became a mode of work that was accessible to me as a young mother."

What parts of your wardrobe do you feel you most identify with? What's in your closet today?

"I mostly identify with long flowing African printed or colorful dresses. The maxi dresses remind me of the dresses I wore as a small child in the 1970s, and the patterns are a combination of my father's Ghanaian heritage and my mother's upbringing in Morocco. My closet is full of maxi dresses and Marco Hall jumpsuits. I love being able to put on one item and be dressed fabulously."

Can you tell us about working collaboratively with your friends and other designers to create special looks? What do these ensembles represent for you?

"I love working with a designer that gets my style. I don't tell them what to create, I just find people who are already on the same vibe. The most I might do is request the same dress or outfit in different colors. I must have at least 10 Marco Hall jumpsuits. I used to sew my own clothing, but I just don't have the time anymore. I would love to do a fashion collaboration eventually."

The various textiles and pigments in your work communicate facets of the Black experience; can you elaborate on why reference points—like history, beauty, and erasure—are seen in your work?

"I want my work to tell the story of my people from our point of view. I try to use colors and patterns that will help communicate the truth about my community. Many times, you will see that the Black contributions to this country have been ignored and deliberately left out and changed, and I want to refute that and set the record straight. Recently, our country recognized the 1921 Massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, of Black Wall Street. This story had been spoken about in my community (and many others like it that were misrepresented as race riots), but it wasn't acknowledged in the mainstream white media, government, or history books.

"I am creating a portrait of Olivia Lee Hooker, who was one of the last survivors of the massacre and recently died at 103 without receiving any justice for the harm that was done to her or her family. The photo I am using is of Mrs. Hooker when she was only six years old, happily perched on a stool in a photographer's studio. I want to celebrate her beauty and innocence by using bright and cheerful colors like yellow, orange, and pink. I also want to suggest the oncoming turmoil by suggesting deep blues and purples creeping in from the edges of the quilt. I use specific African and Dutch wax patterns that have names in West Africa and are associated with wives' tales, folklore, humor, and warnings. One pattern that would work for this quilt would be the print called Macaroni and symbolizes advice that is given from mothers to daughters. Another pattern I'll use is called 'Children Are Worth More Than Gold' and has tiny images of babies in utero and chicks in their eggs. African people looking at this quilt will understand the symbolism being expressed to help tell the story of Olivia Lee Hooker."

What African fabrics, prints, and colors—like those from your father's homeland of Ghana, batiks from Nigeria, and prints from South Africa—are seen in your work?

"I am partial to Kente cloth, which is a woven silk and cotton made in Ghana and was traditionally worn by royalty and people of high social status. I also use a lot of Dutch wax fabric made from a company called Vlisco that has been printing wax fabric since 1840. Vlisco is considered one of the most sought-after and respected brands of wax printed fabric. These fabrics are printed in Holland and then sold in the marketplaces in Africa, and the sellers are called the 'Nana Benz.' A Nana Benz is a wealthy African woman merchant who is so successful she has a big luxury Benz. The Nana Benz rename the fabrics based on what they remind them of. Some of my favorites are 'Si Tu Sors, Je Sors' ('If you leave, I leave'), "Grotto" (which represents a wealthy, heavyset lover), and "Genito" (a pattern that represents a young, handsome, and possibly broke lover).

"I also use South African Shwe-shwe prints and Nigerian Adire cloth. The Adire is a type of tie-dye wax printed cloth that uses symbolic glyphs to communicate messages. For example, a spiral represents the cycle of life, while wavy lines indicate a transition."

Who are typically the subjects in your works? What do they represent?

"The subjects in my work represent my extended family—the African diaspora. Since I am descended from free and enslaved peoples, I won't be able to know all of the people who I am related to by blood. Many Black people call each other brother or sister to acknowledge this. I acknowledge this by treating my subjects like they are family."

You've created portraits of people you've never met and who have never been photographed, like your father's father. What type of preparation goes into this storytelling? What physical details do you feel you must include?

"If I am creating a portrait of someone I've never met or never seen, I will do as much research about them as I can. I will try and find out when and where they lived, what did they do in their life, and what they may have faced. The colors and emotions will be made up by me based on what I've heard or read about that person. If they were known to be cool or calm, I'll use blues and greens primarily. If the person was known to be forceful, passionate, or fiery, I may use reds and oranges.

"Unfortunately, I never saw an image of my grandfather. The only thing I know of him are my father's memories. The fabrics I chose to portray my grandfather were all woven in Ghana and were cut from my father's old dashikis. Many African prints are only sold for a short period of time, so by using vintage African prints I am indicating a time and date for the life of a person."

Has the idea of your work changed in response to what's happening to Black lives in America?

"My work was always a record of who we really are—how we want to be seen—and I think that people were drawn to positive images. Images that tell the truth in the time of an international awakening. I think many people became aware of my work during the last few years, although I have been making the same kind of work for 20 years."

Do you feel you have a responsibility to communicate what you've learned, what you see, what you feel is unjust?

"I taught high-school art in the Newark public schools and at Columbia High School in Maplewood, New Jersey, for 13 years, and being an educator will always be with me. I also was educated at Howard University, an HBCU, that always held up the tenet that those who were fortunate enough to be able to be educated had a responsibility to share their knowledge with the community. Now these drives are a part of me. If I know that my people are struggling, I also know I have an audience and the responsibility to help."

Your work has also communicated beauty culture, like your work seen in a shea butter ad. How has your idea of Black beauty evolved and/or stayed the same in recent years?

"My ideas of Black beauty have remained constant. I was taught that Black is beautiful since I was a tiny child. It wasn't a given to be considered beautiful, being a dark-skinned child of an African parent and a Black American parent. In the 1980s, many Black Americans did not want to necessarily associate themselves with Africa. Colonialism and divisive political tactics caused many people to see themselves as separate and different. My parents worked hard to make sure that we saw ourselves as beautiful and worthy in any shade, hair texture, and body shape, and that's the same way I regard Black beauty today."

What is your typical daily beauty routine? Any go-to products or tricks?

"My typical daily beauty routine consists of washing my face with Korres Greek yogurt cleanser, SKII pitera essence, and Korres or Kiehl's moisturizer depending on how my skin feels that day. I use a gua-sha with a light Korres skin oil for about 10 minutes and then go. About once a week, I use my Nu-Face and an SKII mask for rejuvenation."

What do you hope for the future of artisanship, like quilt making, especially now, at a time when the younger generation is focused on industries like tech?

"I hope that the techniques of sewing, quilting, weaving, and felting can stay relevant in the future. The acknowledgment of traditional women's work as fine art will enrich and open up the art world to so many more possibilities. Although the focus may be on tech now, I think that it is up to the new artists to find ways to hold on to traditional skills while applying them to new technologies."

Shop Bisa's Go-to Beauty Products:

Greek Yoghurt Foaming Cream Cleanser

Facial Treatment Essence

Greek Yoghurt Nourishing Probiotic Gel-cream

Ultra Facial Moisturizing Cream with Squalane

Wild Rose Brightening Absolute Oil

Trinity Complete Facial Toning Kit (6-piece)

Facial Treatment Mask (6-count)

Top photo: Courtesy of Bisa Butler

Want more stories like this?

The Pop Icon Collaborator Turned Indie Darling

A Glimpse Inside Houston's Most Famous Strip Club

More Than a Mock-Up: How Janet Is Etching Her Mark on Hollywood

0 Comments